This follows on from: Generative AI for Genealogy – Part XIII

In the last instalment of this increasingly ambitious genealogy‑AI odyssey, we laid down the foundations of the system. And by “foundations,” I mean the kind of foundations you pour when you think you know what the house will look like, but you’re also quietly aware that you might end up adding a conservatory, knocking through a wall, or discovering that the architect (me) has drawn a door that opens directly into a cupboard.

The core idea was simple enough:

- Break the user’s question into sub‑questions

- For each sub‑question:

- Run the retrieval agent

- Let it call whatever “tools” it needs

- Receive the tool data

- Produce an answer

- Gather all the answers

- Stitch them into a final response

Shockingly, this works. Even more shockingly, it works well, despite relying on a local LLM that occasionally behaves like it’s running on a potato.

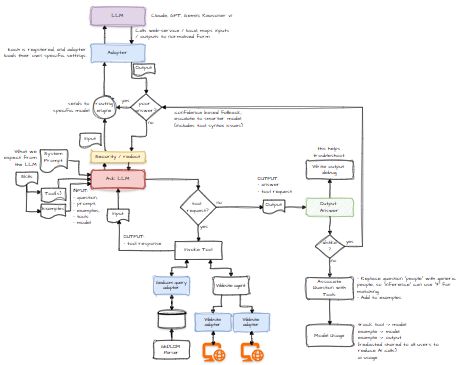

But as the system evolves, it’s drifting away from the original straw‑man diagram I shared earlier:

This is normal. Architects sketch intent; reality sketches corrections. Blueprints are aspirational. They’re the “ideal world” version of events, where everything is neat, labelled, and nobody has to duct‑tape a server at 2 a.m. because a process decided to eat all available RAM.

You can delay decisions forever in pursuit of perfect clarity, but that usually results in… well, more delay. As Donald Rumsfeld famously said, there are “known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns.” In software terms: things you understand, things you know you don’t understand, and things that explode unexpectedly on a Friday afternoon.

I could have spent weeks reading other people’s architectures and copying their patterns. But that would have taught me very little about my system. I wanted to learn by doing — and occasionally by doing it wrong.

The End‑State: A Small Army of Agents

My goal is to build a product that can:

- Write life stories in prose → writing agent

- Answer questions from GEDCOM data → retrieval agent

- Query external sources via adaptors → research agent

- Solve puzzles, hypotheses, and constraints → inference agent

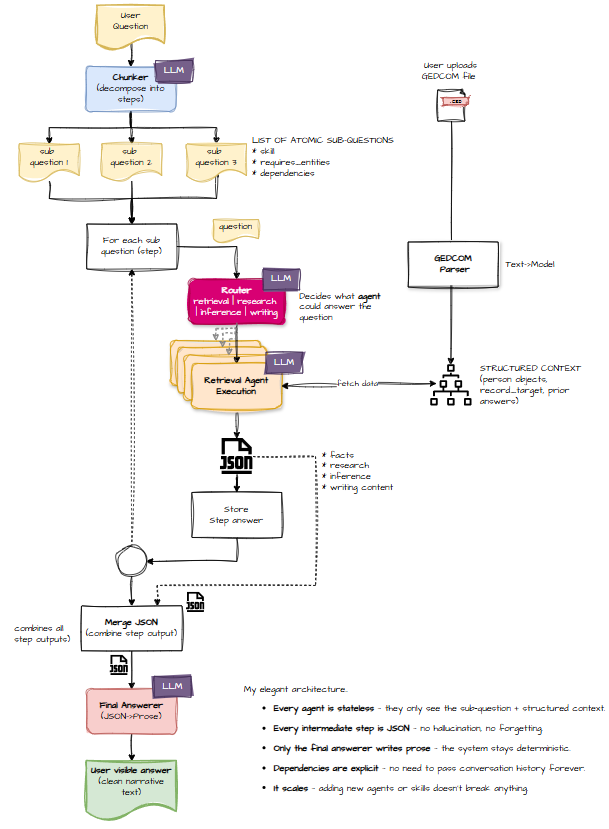

To get there, we need to dismantle the straw‑man and rebuild it using what we now know. The next iteration looks more like this:

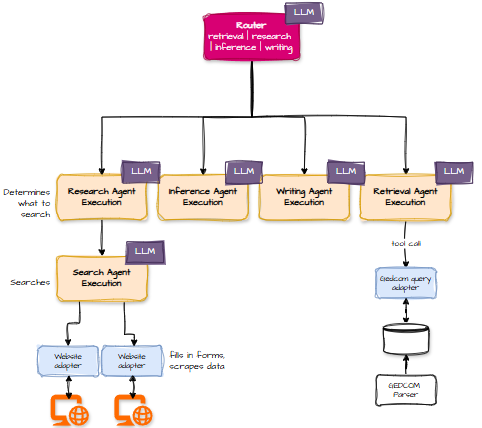

And zooming in on the router:

Two of these flows — retrieval and research — are already well‑defined because I’ve built them. The writing agent works, though it needs some polishing. The inference agent exists, but I haven’t yet thrown anything truly diabolical at it. (No “second cousin twice removed via marriage to the half‑uncle” puzzles yet.)

The biggest architectural shift is this:

An LLM now decides which agent should handle each sub‑question.

This is both powerful and slightly terrifying, like giving a toddler the TV remote and discovering they somehow ordered a documentary about 18th‑century shipbuilding.

From here on, I’ll be more guarded about prompts and internals — not because I’ve suddenly become mysterious, but because I’d like to keep the option of turning this into a paid service. Diagrams and flows, however, remain fair game.

Tool Output: JSON Everywhere

In the early days, the flow was:

User → LLM → Answer

Tools returned JSON, but the LLM was told to ignore that and produce a nice human‑readable response.

In the updated architecture, you’ll notice something new in the diagrams: JSON.

Rumour has it that LLMs love JSON. They want to output JSON. They dream in JSON. And the final‑answerer is perfectly happy to take that structured output and turn it into a polished narrative.

I say “rumour” because I haven’t yet updated all my skills to output JSON. That’s this afternoon’s job. If you hear screaming, that’s why.

Spiralling Token Counts (a.k.a. The Budgetary Horror Section)

With LLMs appearing in multiple stages of the pipeline, token usage becomes a real concern.

Take this example:

“If Lisa is a sibling of Bart, and Homer is the father of Maggie, what relationship is Marge?”

The system eventually concluded:

“Marge is the mother of Bart and Maggie.”

Lovely. Except it took 43,000 prompt tokens and 738 output tokens to get there.

Cost: half a penny.

Half a penny doesn’t sound like much… until you realise that users will ask far more complex questions, far more often, and suddenly your profit margin is being eaten alive by genealogical hypotheticals.

There are ways to optimise:

- Use newer, more capable models

- Reduce examples and prompt scaffolding

- Simplify skills

- Generalise tool calls

For example:

“Where was Dave born?” → get-birth-location:Dave

This can be abstracted to:

“Where was {person} born?” → get-birth-location:{person}

If the system can recognise these patterns, we don’t need an LLM to convert every question into a tool call. I call this adaptive learning, and it’s one of the easiest wins for reducing token burn.

Feedback: Like / Dislike

In the original straw‑man, I included feedback buttons.

I haven’t forgotten them.

But their impact is subtler than you might expect.

My plan is for the AI to mark its own homework — meaning it will spend extra tokens verifying that its answer makes sense. (Yes, this increases token usage. Yes, I’m aware of the irony.)

A “like” button doesn’t do much at first. It reassures the user that we care, and it may log the Q&A pair for future analysis.

A “dislike,” however, is wired into the system. It tells the AI:

“Try again — something went wrong.”

Unlike code, where a compiler gives you a neat error message, genealogy answers don’t come with stack traces. So the system may need to ask the user what category of error occurred:

- Wrong data

- Wrong reasoning

- Wrong conclusion

- Wrong tone

- Wrong century

The system can then retry with that context. Whether it retries the whole pipeline or just a specific step is still to be determined.

Where’s Redaction?

Just because I’m using cloud models doesn’t mean I’m happy to leak personal data. Redaction is still on the roadmap — just slightly lower down the priority list.

The challenge is how to do it safely.

If I send unredacted data to an LLM to identify entities, and then redact them afterwards, that defeats the purpose. One option is to run a small local model in the cloud (e.g., via ollama) to perform redaction before anything touches a third‑party LLM.

This is solvable — just not solved yet.

What’s Next?

Testing.

Because every change, no matter how small, has the potential to break something that previously worked. And nothing says “fun weekend” like debugging a system that insists a great‑grandmother is also her own nephew.

Click Like.