This follows on from: Generative AI for Genealogy – Part XIV

Evolution (or: How I Discovered My Ignorance the Hard Way)

In the previous instalment, I casually dropped a more complex architecture diagram into the mix and then… didn’t explain it. At all. So let’s fix that before someone reports me to the Software Architecture Police.

The journey began with this beautifully naïve little setup:

It looked so clean. So elegant. So deceptively simple. And to be fair, it actually worked—right up until it didn’t. First came the cracks. Then the holes. Then the “why is this on fire?” moments.

One of the biggest problems in chat systems is figuring out what the user is referring to. In genealogy, this is not a minor detail—it’s the whole game. If you can’t handle follow‑up questions, you don’t have a genealogy assistant; you have a confused parrot.

Take this classic:

- “When was my cousin born?”

- “Who did they marry?”

Two questions, one pronoun, and a whole world of potential chaos. This is called subject resolving, and it’s the difference between a helpful assistant and one that confidently tells you your cousin married himself.

Or:

- “Who is Bart’s mom?”

- “Who is his dad?”

If “his” resolves to Bart’s mom instead of Bart, you’re going to get emails. Angry ones. Possibly with screenshots.

My early idea was that the conversation history would magically solve all of this. Just keep feeding the LLM more and more context:

- question 1

- question 1 + answer 1

- question 1 + answer 1 + question 2

- question 1 + answer 1 + question 2 + answer 2 + question 3

You get the idea. A sort of ever‑growing snowball of context. And honestly? It worked surprisingly well. “Reasoner v1” didn’t panic. I sat there feeling smug, sipping tea, imagining I had cracked conversational AI.

Then reality tapped me on the shoulder and whispered, “Bless your heart.”

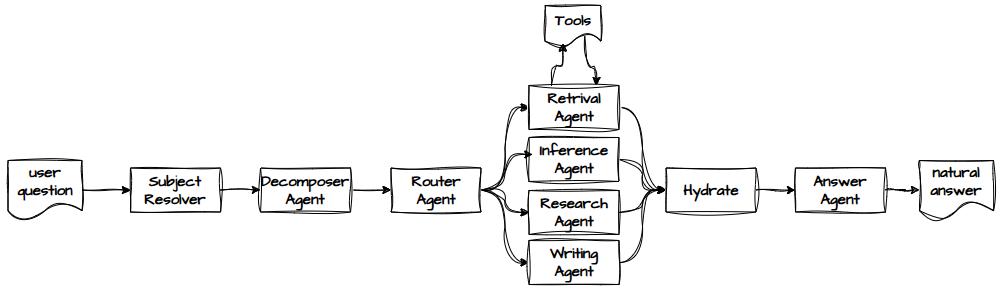

So I moved to a more conventional architecture—one that looks like it was designed by someone who has actually read a paper or two:

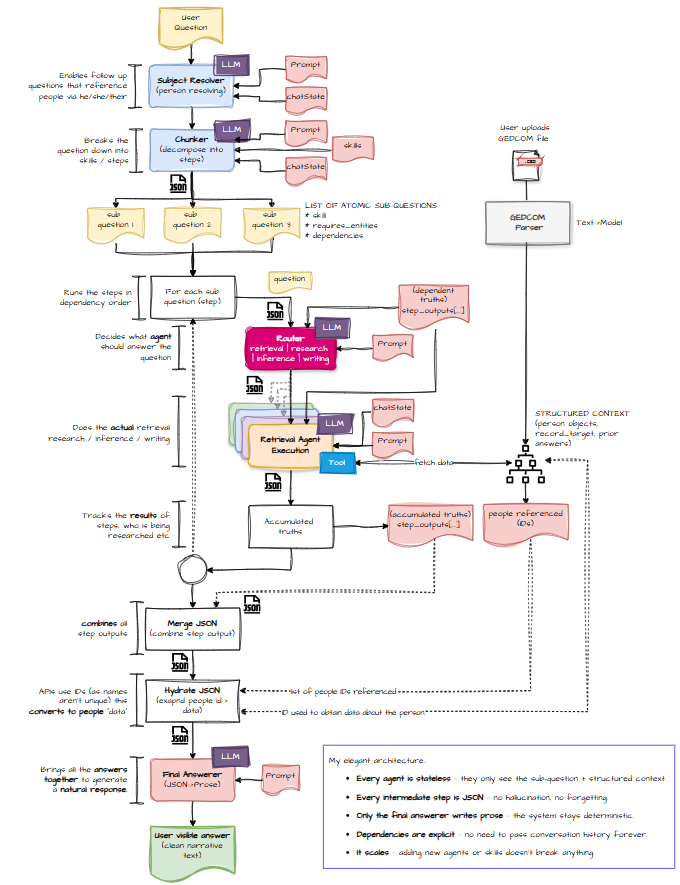

If you prefer colour (and who doesn’t?), here’s the same thing but with more visual dopamine:

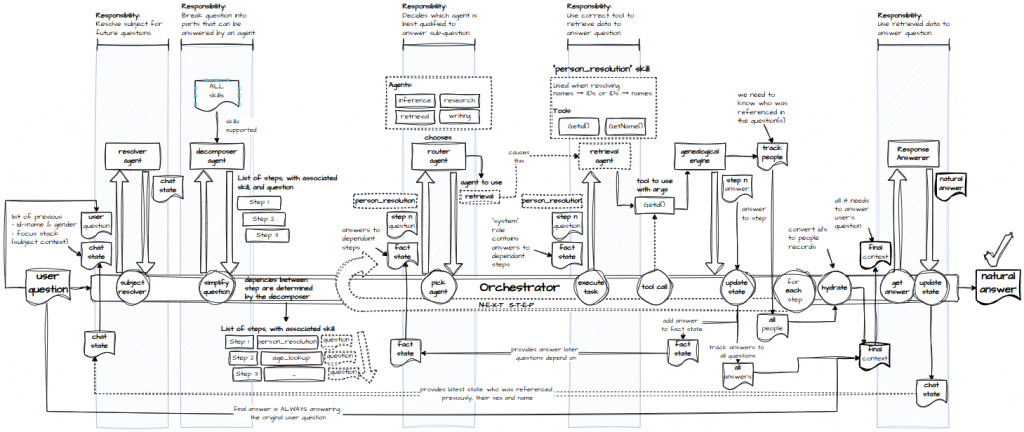

And if you want to see it as a machine—an orchestration engine with all the cogs exposed—here you go:

Since the last post, I’ve added a few more components. Let’s walk through the whole thing, step by step, and explain why each piece exists.

- The user submits a question.

- The subject resolver figures out who or what the question is actually about—referents, subjects, couples, the whole messy family.

- The decomposer agent breaks the question into logical steps. It decides what needs doing, not who will do it. For example:

- Resolve a name into a person ID

- Look up the spouse of the person from step 1

- With steps defined, we need to execute them in the right order. Dependencies matter.

- The router agent looks at each step and decides whether it requires retrieval, research, writing, or inference. It then spins up the appropriate agent.

- For data, the retrieval agent turns the step into a tool call.

- The GEDCOM query engine receives the tool call and returns the data.

- Finally, the answer agent takes all the results and produces a natural‑language response.

Context

Once you break the system into multiple sub‑agents, you can’t rely on “just pass the whole conversation” anymore. Some knowledge needs to be shared, but not all of it. For example:

- The router needs to know what data we already have so it can decide whether a step is retrieval or inference.

- The decomposer needs to know which people are already in play to determine the correct steps for a follow‑up question.

- Steps depend on each other, so we pass data forward on a “need‑to‑know” basis—like a spy agency, but with fewer trench coats.

Hydrate

Genealogy is full of repeated names. I have fourteen William Christians in my tree. Fourteen. If you ask about “William Christian,” you might as well ask about “that guy with hair.”

So the system resolves names into IDs early on. But by the time the answer agent gets involved, it’s holding a handful of IDs and no names. Hydration fixes that: given an ID, fetch the person’s full data once and reuse it.

If you’ve built systems like this, you’re probably shouting “You missed a bit!” And yes, I probably have. But look how far I’ve come.

If you’re learning, you might ask: “What made you change?” and “How did you know what to do?”

Honestly? Blame GPT. In a good way.

As I hit issues, we talked through options. I wrote code while GPT helped other people, possibly dreaming of having a Grok owner who lets it misbehave more than the OpenAI overlords allow.

Through those conversations, I learned how the “Big Boys” do it. How GPT knows this is… mildly unsettling.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing.

At one point, GPT gave me a series of tool‑syntax recommendations that felt like being dragged through three different coding styles in a week:

- First: “Your custom syntax like

get-motheris great! Very LLM‑friendly.” - Later: “Actually, you should use Python syntax. LLMs love Python.”

- Then: “Actually actually, you should use JSON tool‑calling syntax.”

By the third rewrite, I was questioning my life choices. I may have expressed my feelings to GPT. I may have felt guilty afterwards. But honestly, this was as much on me as on it. I had long conversations, huge prompts, days of iteration. Even I couldn’t remember half the good advice without pasting it into a Word doc.

And at no point did I ask GPT for the best or correct way to do something. My way worked, so I stuck with it. The journey—mistakes included—taught me more than a perfect answer ever would.

I still love working with GPT. This experience didn’t change that. It just changed how I design with it.

One big shift: I moved from using GPT in the browser to using GPT‑5.2 Codex in VS Code. Pasting giant prompts into a browser while GPT tries to understand the surrounding code is like trying to diagnose a gearbox failure by listening to it from across the room. GitHub Copilot is simply better for that kind of work.

I still use browser GPT heavily. We even had a great follow‑up chat about jailbreaks—the LLM kind, not the HM Prison kind—which I’ll cover in a future post. And GPT still helps make these blog posts fun to read.

Next up: today’s main topic—testing.