Where Did My Revenue Protection Go?!

There’s a special kind of horror that only hits you after you’ve built something cool. You sit back, admire your creation, and then realise you’ve accidentally sawed off the branch your business model was sitting on.

In my case, the moment came when I realised that by moving from a fat client to a web‑app, I had quietly obliterated two of my core revenue protections:

- Restricting users to a 30‑day trial period

- Preventing license sharing across multiple computers

The second one isn’t catastrophic — if a second user signs in, it boots the first one out. Not perfect, but it limits the damage. It’s like having a guard dog that only sometimes chases intruders, but at least barks loudly enough to scare a few away.

But the first one? That’s the real problem. If someone’s trial expires, absolutely nothing stops them from creating a new account. Or ten. Or a hundred. And then I starve, lose my home, and end up writing genealogy software on a park bench using free Wi‑Fi from a nearby café.

Codex’s Suggestions (and Their Limitations)

I asked GPT Codex for advice, and it responded with a list that sounded like it had been lifted straight from a SaaS security handbook:

You’re missing that trials must be tied to a stronger identity than just username.

Common mitigations:

- Require verified email (1 trial per email; block disposable domains).

- Require payment method to start trial (no charge until trial ends).

- Rate-limit and cap trials per IP/device/browser fingerprint.

- Detect reuse patterns and block/flag automatically.

- For B2B, issue trials by invite or sales approval.

No single signal is perfect; combine several and enforce server-side.

All very sensible. All very standard. All completely missing the point.

The identity wasn’t the username. That was the problem. Users could create ten accounts faster than I could say “please don’t bankrupt me.”

And while the suggestions were reasonable, they came with caveats:

- Blocking disposable domains? Useless. Anyone can spin up multiple Outlook addresses before breakfast.

- Asking for payment details upfront? I don’t want to scare people away before they’ve even tried the thing.

- Invite‑only trials? No thanks. I want people to fall in love with the product, not apply for a visa.

So I asked Codex about device fingerprinting. It happily rattled off a list of browser signals like it was reading from a spy manual:

A typical “device ID” is a hash of relatively stable browser signals. Example inputs (concatenate, then SHA‑256):

navigator.userAgent,platform,language- Timezone offset

- Screen width/height, color depth, pixel ratio

hardwareConcurrency,deviceMemory- WebGL vendor/renderer (from WebGL debug info)

- Canvas fingerprint hash (draw text + shapes, read pixels)

- Audio fingerprint hash (offline audio oscillator render)

Device Fingerprinting: MI6 for Genealogy

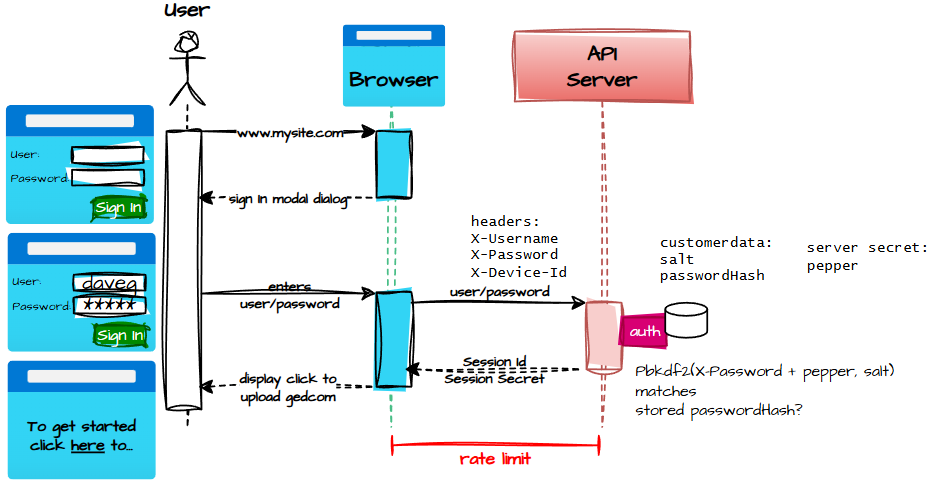

In the end, I settled on something pragmatic:

- The client generates a stable device hash during registration/authentication.

- The server stores device + IP per account.

- Duplicate registrations from the same device or IP are blocked.

- Sign‑ins must come from the same device.

Not perfect. Not bulletproof. But workable for now.

When Best Practice Comes Knocking

I woke up the next morning thinking, “What have I done?”

Because here’s the thing about vibe‑coding:

- It writes sensible code.

- It reviews it.

- It finds security issues.

- It fixes them.

- It adds features when asked.

- It does all this with the calm confidence of a junior developer who has never once been paged at 3am.

But it doesn’t think. It doesn’t challenge assumptions. It doesn’t say, “Dave, mate, are you sure you want to do that?”

And I should have known better. I’ve built secure web apps for years. I know the rules:

- Never store passwords unencrypted — always store a hash.

- Hashes alone aren’t secure — rainbow tables exist.

- Hashes must be protected with a salt (client‑side) and a pepper (server‑side).

Yet in my quest to avoid storing anything personally identifying, I broke the pattern. Worse, when I added revenue protection, I violated my own rule by storing the IP address.

Did Codex warn me? No. Not even a polite cough. It just did what I asked, like an obedient golden retriever who will happily fetch the stick even if you throw it into a volcano.

Vibe coding ≠ senior engineer. It’ll get there, but Codex wasn’t there at the time of writing.

So I rebuilt the authentication properly.

Doing It Properly

What did I lose by doing it the right way?

My mind? No — that went years ago.

We were already tracking device ID and IP address, so we might as well follow best practice and sleep at night.

And hopefully the lesson is clear: Codex didn’t call out the fact I was violating security fundamentals. It just silently complied.

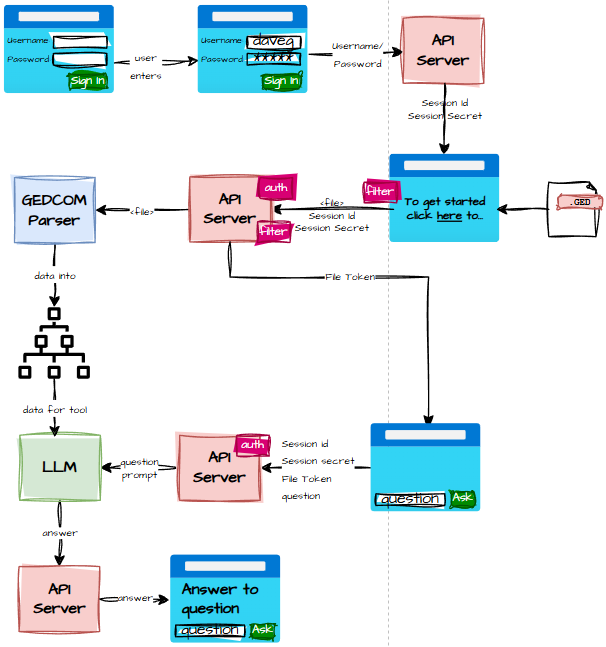

Once everything was fixed, I added:

- a 30‑day trial

- a 14‑day nag‑grace period

- payment via Stripe

And yes — I own all the code it wrote. Which means I need to be very careful with the payment side. Nothing wakes you up faster than the thought of accidentally charging someone £4,000 because of a missing decimal point.