Testing My Patience

How do you begin testing a machine like this?

Badly. Very badly.

My early approach was the classic “throw random questions at it and see what explodes.” Something breaks, I tweak a prompt or a line of code, try again, and—surprise!—now a different question breaks. It was like playing whack‑a‑mole with a blindfold on and the moles are armed.

To make matters worse, “Reasoner V1” had the performance profile of a sedated snail that’s been stepped on twice. Some agent calls took twenty seconds. One took 773 seconds. That’s not a response time—that’s a cry for help.

Most of my build time has been spent waiting for the LLM to finish thinking, which is why I’ve been migrating toward GPT as the backend. At least then, when something takes ages, I can pretend it’s because GPT is pondering the mysteries of the universe rather than stuck in a mental cul‑de‑sac.

GPT Woes

Of course, moving to GPT comes with its own set of “life lessons.” The kind you don’t ask for.

Financially, you have to be careful. Cloud vendors let you cap your spend, but that doesn’t protect you from the moment your code goes rogue and burns tokens like a toddler with a box of matches. Or when some eejit tries to jailbreak your LLM for “research purposes,” which is hacker‑speak for “I wonder what happens if I poke this.”

Once the tokens are gone, the product stops. For everyone. Cue brand damage, angry emails, and late‑night calls that begin with “So… the system is down.”

To avoid this, I’ve capped each session. When it hits the limit, it stops. No excuses, no exceptions. It’s like a strict parent: “I don’t care who started it, we’re done.”

This applies to testing too. It’s a good reminder of how many tokens we’ll inevitably burn just trying to make sure the thing works.

Getting It Right

The feature list lives here: https://aimlfun.com/the-gen-ai-genealogy-feature-list/

It’s a broad capability list, not a set of fixed questions. The idea is simple: if the system can handle these, it can handle most things users throw at it. (Except maybe “Who is my real father?”—that one’s always a gamble.)

For a good customer experience, we need to consider two things:

- All the questions and tasks we plan to support. They must work end‑to‑end.

- Each agent must work in isolation. The whole system is only as strong as its weakest link.

That’s a lot of questions. And they vary wildly in complexity. Some require context, some require multi‑step reasoning, and some require the decomposer to do interpretive dance.

Item 1 is easy: ask the orchestrator a question as if you’re the user, and check the answer. This becomes a list of questions and expected outputs. You can’t match exact answers—LLMs are too creative for that—so you check for “contains” and “does not contain.” Example: “Who are Harry Potter’s parents?” → expect to see “Lily Evans” and “James Potter.” Except the GEDCOM I found online said “Lilly Evan,” because apparently muggles don’t care about data quality.

Item 2 is where the real fun begins.

Take the router. The decomposer gives it a single step, and the router categorises it so the correct agent is invoked. Singular matters. The router must never receive something that the decomposer would break into sub‑steps. I know this because I walked straight into that trap and fell face‑first.

Then there’s the decomposer itself. It has to take a gazillion questions and decide how to break them down. That means trying the question, scraping the answer, and verifying correctness. It’s like training a dog, except the dog is made of probabilities and occasionally hallucinates.

The writer, inference agent, and answerer will be even harder to test. It’s going to require careful thought—and possibly begging GPT for the “best” or “correct” approach. Testing an LLM is not like testing a function that adds two numbers. You can’t brute‑force every input. You hope the algorithm is deterministic, unlike the infamous Pentium FDIV bug (EXTERNAL: Wikipedia).

With an LLM, even temperature 0 doesn’t save you. The same input yields the same output, sure—but the inputs come from other agents, and those are infinite. This is the kind of thing that causes sleepless nights.

If anyone wants to see how the test module works, I’m happy to share.

To get started, I pasted the feature questions into a QUESTIONS.md.

Then I asked CODEX to build the test harness. I explained I wanted YAML input files, that each agent needed to be called, and CODEX… sort of wrote the logic. It didn’t compile, but it wrote enough to save me hours. It even remembered to add an “enabled” flag so I can disable tests while focusing on the broken ones. This is essential—you still need to run everything before shipping, but you don’t want to burn tokens while debugging one stubborn test.

I also asked CODEX to generate the YAML test file. It did. I’m still discovering cool tricks like that.

On the topic of tokens: Reasoner V1 needs so much guidance that using those prompts in production would destroy my profit margin. One thing CODEX can do is convert prompts to another LLM—some are half or a third the size. Whether the GPT‑specific prompts work, I don’t know. I haven’t been brave enough to hook it up yet.

Another tip: get CODEX (or similar) to write your README.md files. I create an empty README.md in each core folder and ask it to explain the important parts for another developer. It even draws Mermaid diagrams. If you’re a dev manager, try it. Then decide which sections you want as standard and give the team the prompt.

Before you question whether I understand testing, I do. I built front‑end testing for my fintech using Playwright, including compound tests. I wrote API tests. I’ve done the whole thing.

Which is why I’ve skipped a few items:

- UI – currently the least of my problems. The SPA is simple-ish. It’s basically a chat app with a login. I barely wrote any code (vibe‑coded it). I’ll test it properly later, maybe even write about using Playwright with an SPA.

- APIs – also vibe‑coded with tweaks. They’re simple and easy to vet. But they still need proper API tests. I might use Playwright or write a C# harness.

- Functions – the eternal debate. TDD is a crock. There, I said it. With context: I test everything thoroughly as I build it. I don’t move on until it works. Is that TDD? No. I don’t write mountains of tests. Could I go more TDD? Maybe. But it would kill velocity. I don’t believe anyone writes a test for every function and still achieves greatness—unless the greatness is “most lines of code written to prove something you already knew.” For me, testing is about identifying the high‑value areas and focusing there.

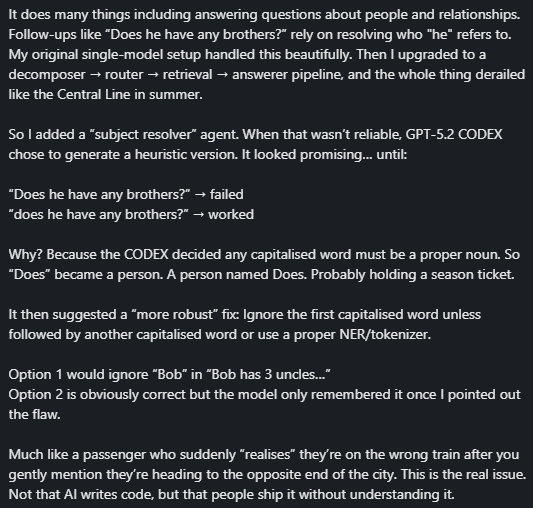

And then there’s this gem I posted on LinkedIn (excerpt):

This is why heuristics for subject resolution terrify me. They break the moment you switch languages or encounter someone who doesn’t capitalise proper nouns. And the code CODEX wrote? Best described as #*$@*! The “fix” it proposed, also #*$@*! Thankfully, it’s temporary until I fully migrate to GPT.

But this raises a question: who writes the tests? Does CODEX mark its own homework? How do you know the tests are complete? How do you catch all the bugs?

Systems are complex. No bug matters—until it does. And then it can ruin your brand.

I now have the basics in place for nearly everything. The next steps are moving to a real LLM and finishing the tests.

One area I might write about soon is research. Today it suggests; tomorrow it needs to scrape. I also want to introduce “like/dislike” feedback and self‑regulation—auto‑dislike and retry.

I’ll leave you with one final LLM horror story.

Did you know an LLM can return JSON… that is malformed?

Oh yes.

I’ve seen:

- A missing

]in an array. - A list like

["a","b",...]—which is not, in fact, valid JSON.

Oops. Forgot the trigger warning.

Until next time… Which is now here: Generative AI for Genealogy – Part XVI