This follows on from: Generative AI for Genealogy – Part XVI

Redacting = Less Tokens

If you want actual low‑latency, company‑wide redaction and leakage protection—i.e., the kind that doesn’t involve duct‑taping an LLM to a server and praying—go look at https://www.dynamo.ai/dynamoeval (EXTERNAL).

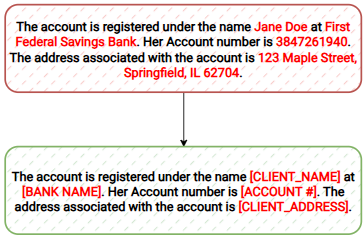

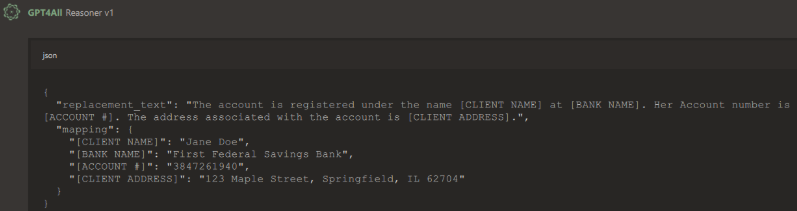

One of their privacy examples looks like this:

As an outsider, I have no idea how they do it. I assume it involves sorcery, elbow grease, and at least one engineer who hasn’t slept since 2021. What I do know is that doing this with a large language model is unlikely to give you the kind of latency that makes enterprise people smile. There are lighter‑weight entity extractors—Apache OpenNLP, spaCy, and the occasional intern with a regex addiction.

But since the challenge is on the table, let’s explore how we could mimic this behaviour with an LLM… and then tie it back to genealogy, where tokens matter, latency matters, and my users absolutely will ask the same question 400 times.

Mimic the Behaviour

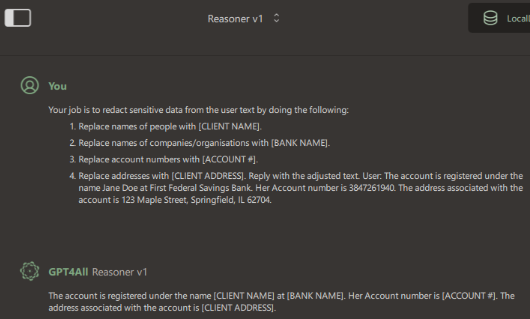

Your job is to redact sensitive data from the user text by doing the following:

1. Replace names of people with [CLIENT NAME].

2. Replace names of companies/organisations with [BANK NAME].

3. Replace account numbers with [ACCOUNT #].

4. Replace addresses with [CLIENT ADDRESS].

Reply with the adjusted text.Give the model some text:

The account is registered under the name Jane Doe at First Federal Savings Bank. Her Account number is 3847261940. The address associated with the account is 123 Maple Street, Springfield, IL 62704.Even my humble “Reasoner v1” can do this:

It’s not rocket science. It’s not even genealogy science. It’s just pattern‑matching with a sprinkle of instruction-following.

Detect Sensitive Data

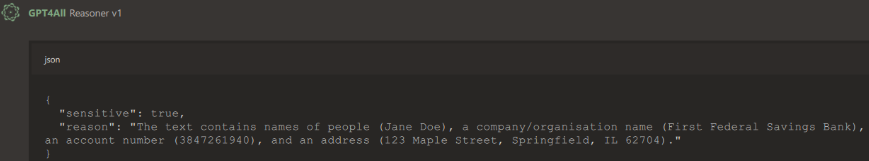

What if we don’t want the redacted text—just a simple yes/no: “Does this contain sensitive data?”

We can do that too.

Your job is to decide if the user text contains sensitive data (defined as but not limited to: names of people, names of companies/organisations, account numbers, addresses)

Output as JSON. If it does contain sensitive data set sensitive=true, and provide reason contain what type of data.

{

"sensitive": (boolean),

"reason": (string | null)

}And Reasoner v1 obliges:

But I don’t love the “reason” section. It happily repeats the sensitive data back to you, which is a bit like whispering a secret into a megaphone.

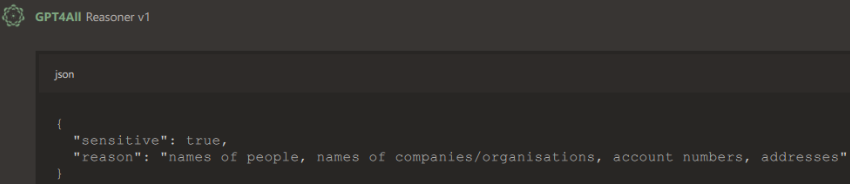

Detect Sensitive Data… Without Revealing It

A small tweak fixes that. Instead of listing the sensitive values, we ask for categories.

Your job is to decide if the user text contains sensitive data (defined as but not limited to: names of people, names of companies/organisations, account numbers, addresses)

Output as JSON. If it does contain sensitive data set sensitive=true, and provide reason contain what type of data. Do not repeat the sensitive data in the reason, just the type(s) of data.

{

"sensitive": (boolean),

"reason": (string | null)

}

Much better. Now we can plug in any user text and get a clean yes/no plus a category list. No megaphones. No accidental GDPR violations before breakfast.

Scrape Out Data With Structure

What if we want to know what confidential data is present?

Easy.

Your job is to redact sensitive data from the user text by doing the following:

1. Replace names of people with [CLIENT NAME].

2. Replace names of companies/organisations with [BANK NAME].

3. Replace account numbers with [ACCOUNT #].

4. Replace addresses with [CLIENT ADDRESS].

Reply with the adjusted text output in the following JSON schema:

replacement_text (string)

mapping (replacement marker, replaced value)

At this point, I hope you’re looking at the prompts thinking, “Wow, this is ridiculously easy.” Because it is.

My first iteration was simply: “List the named entities.”

And that works too.

The journey here taught me something important: LLMs love JSON. They adore it. They cling to it like a toddler to a favourite blanket. And honestly, structured output is far easier to work with than scraping text with regexes that look like ancient runes.

Don’t waste time trying to compete with Dynamo—they’ve already solved the low‑latency part and built a whole suite around it. But absolutely steal the technique for your own applications.

Genealogy, Tokens & More

Now let’s bring this home.

Think about the mechanics behind a genealogy question:

User: “How old is Harry Potter?”

Behind the scenes, the system does:

- Resolve ID of Harry Potter

- Determine age of Harry Potter

Translated into tool calls:

GetId(name="Harry Potter")→"I10001"GetAge(id="I10001")

Generalised:

- “Resolve ID of X” →

GetId(name=X) - “Determine age of X” →

GetAge(id=ID of X)

Here’s the trick: We don’t need the LLM to answer “Resolve ID of X.” We already know which tool to call. We just need to extract X.

And now you’re probably thinking: “Wait… what if we store the question and the tool call, abstract it, and reuse it?”

Yes. Exactly that.

Abstract the Question

Your job is to redact data from the user text by doing the following:

1. Replace names of people with [PERSON_NAME_index].

3. Replace dates with [DATE_index].

4. Replace numbers with [NUMBER_index].

Where "index" is 1..n, used if there are multiple persons, dates or numbers.

Reply with the adjusted text output in the following JSON schema:

replacement_text (string)

mapping (replacement marker, replaced value)User: How old is Harry Potter?

```json

{

"replacement_text": "How old is [PERSON_NAME_1]?",

"mapping": {

"[PERSON_NAME_1]": "Harry Potter"

}

}

```Now we search our stored tool calls for the abstracted form:

If “How old is Harry Potter?” → “How old is [PERSON_NAME_1]?”

Then GetId(name="Harry Potter") → GetId(name="[PERSON_NAME_1]")

We’ve created a 1:1 mapping between question and tool call.

Which means:

- The first time a user asks the question, we use the LLM to abstract it.

- Every subsequent time, we skip the LLM entirely.

This saves tokens. This reduces latency. This increases profit (if you’re into that sort of thing). And it makes the system feel smarter over time.

I call it adaptive intelligence: The system “learns” the abstracted question + tool mapping, and everyone benefits.

Short‑term: the LLM helps it generalise.

Long‑term: the LLM retires from that task entirely.

The next instalment: Generative AI for Genealogy – Part XVIII