The Two Pillars of a Research Agent

To build a research agent that can actually help with genealogy, you need two things:

- A way to scrape the data

- A way to make sense of the data

This is the first build, not the eighth. I’m going to miss things. I’m going to make choices that future-me will look back on with a mixture of fondness and mild embarrassment.

But that’s the point.

“Start when you have enough, not when you know everything.” If you wait for perfect clarity, you’ll never start. If you start early, you’ll discover your mistakes sooner — and that’s where the real progress happens.

Reverse procrastination: it’s a thing.

Scraping Data

Decode the Form: Disassembly Required

If the internet were just raw, unformatted data and your browser slapped a coat of paint on top, life would be simple — bleak, but simple. We’d all be living in a world that looked like the mid‑1990s, before CSS arrived and saved humanity from <font> tags and table‑based layouts.

But that’s not the world we live in. We live in a world where websites are designed for humans, not for people like me who want to quietly siphon off their data and feed it into an AI.

FreeBMD is no exception. It’s a brilliant resource, but it was absolutely not built with “Dave’s research agent” in mind.

So we’re going to scrape it. Manually. With nothing but determination and a large language model as our emotional support animal.

I’m not here to teach HTML — the internet is already full of excellent tutorials, and most of them are less sarcastic than I am. Instead, we’re going to focus on the mechanics of the current FreeBMD UI, because understanding the form is the first step to reverse‑engineering it.

Step 1: Open DevTools and Brace Yourself

Head to the FreeBMD “Search” page, hit F12, and use the “select an element” tool to poke at the first checkbox. Underneath all the layout scaffolding, you’ll eventually find something like:

<form method="POST" action="/cgi/search.pl" enctype="multipart/form-data" onsubmit="return validate()">

.. inputs

</form>This tells us a few things:

- The form POSTs to search.pl — a classic CGI script.

- There’s some JavaScript validation to prevent obviously impossible searches (e.g., “Find Grandma who died in 2014” when the dataset ends in 2000).

- Everything we care about is buried inside this

<form>block, wrapped in a labyrinth of<table>tags used for alignment.

Inside the form, the important bits look like this:

<input type="checkbox" name="type" .../>— the Birth/Marriage/Death selectors<select name="districtid" id="districtlist" size="14" multiple="multiple" .../>— the district multi‑select<input type="text" name="surname" .../>— the surname field- …and so on.

Then we get to the “Find” button, which — for reasons known only to the original developer — is implemented as an image with an onclick handler:

<input type="image" name="find" src="/btnFindLg.gif" onclick="pressed(this,"/btnFindLgP.gif"); checkData=1" .../>

It’s charming. It’s retro. It’s also mildly inconvenient.

I Searched for “William Shakespeare” (Not That One)

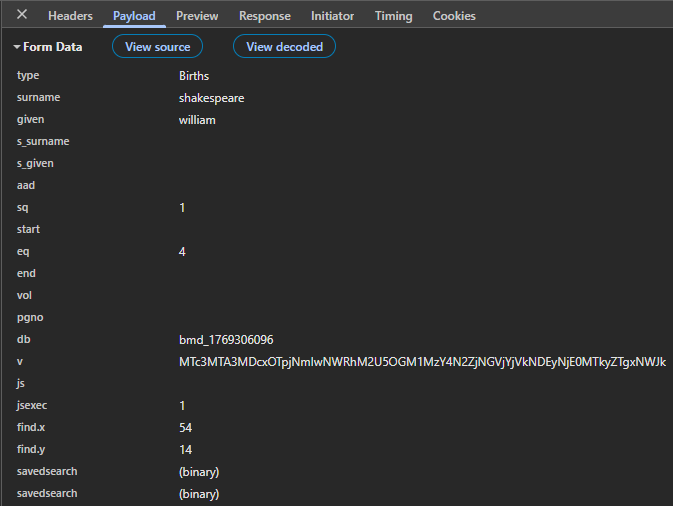

To see what the form actually sends, I searched for “William Shakespeare” (a 19th‑century one, not the bard). The POST variables look like this:

A few quirks immediately stand out:

s_surnameis used for mother’s maiden name and spouse’s surname.s_givenis used for spouse’s given name.- Some fields are overloaded depending on the record type.

This is the kind of thing you only discover by spelunking.

Understanding FreeBMD search results

In a typical modern app, you’d expect something like:

select * from people where surname = 'shakespeare' and given = 'william'…and then you’d get JSON back. Or at least structured HTML.

FreeBMD does not do this.

Instead, the results page contains:

- HTML

- JavaScript

- A proprietary compressed data format

- A 3000‑record limit

- And a rendering pipeline that runs entirely client‑side

Honestly? It’s clever. Annoying for me, but clever.

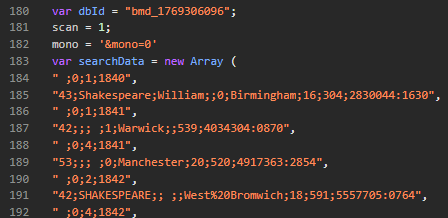

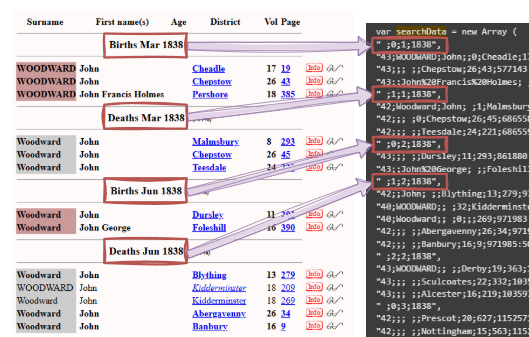

The developer clearly understood that sending 3000 full HTML rows would be huge. So instead, they compress the data into a JavaScript array and let the browser unpack it.

For our use case — scraping — this is… less ideal.

You can’t just “grab the table.” There is no table. There’s a JavaScript function that creates the table.

That function is showEntries(entries, plaindisplay) in search.js.

The Data Format (A Delightful Puzzle)

The entries array contains two types of rows:

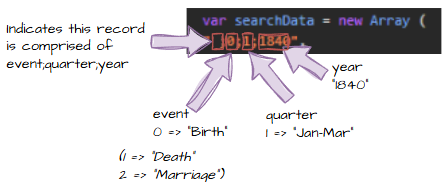

1. Event headers

If a row begins with a space " ":

" 0;1;1892"This means:

- Event type (0=Birth/1=Death/2=Marriage)

- Quarter (1/2/3/4)

- Year (1837-2000)

2. Actual records

Otherwise, it’s a record:

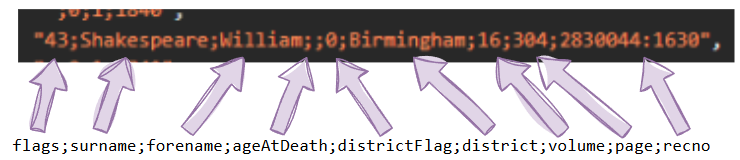

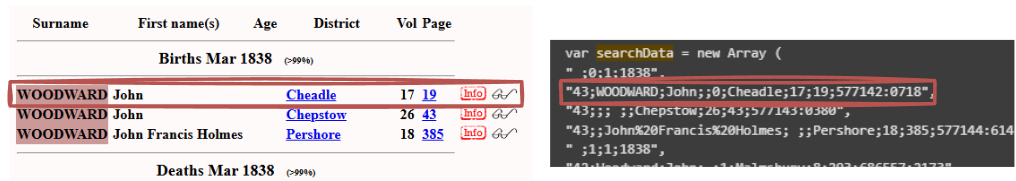

flags;surname;forename;ageAtDeath;districtFlag;district;volume;page;recno

Where:

flagsis a bitmap (bolding, missing spouse, double‑keyed, etc.)districtFlagindicates whether the district is abbreviatedrecnois the internal record number

To make this clearer:

Then:

And finally:

Plus a full mapping example:

It’s genuinely elegant.

It’s also genuinely inconvenient when you want structured data.

More Than 2000 Lines of C# Later…

I did what any sensible engineer would do: I asked CODEX to help.

CODEX responded by making a complete pig’s ear of it.

Not maliciously — just enthusiastically wrong.

It looked at the HTML and did what LLMs do: It tried to be helpful. It hallucinated field meanings. It guessed at semantics. It confidently invented things like ageAtDeath because it saw a number and thought, “Sure, that’s probably it.”

It wasn’t thinking like a senior developer. It was thinking like a junior developer who wants to impress you by finishing early.

And honestly? Fair enough. It’s not trained to reverse‑engineer bespoke compression formats from 20‑year‑old CGI scripts.

This isn’t a criticism of CODEX. It’s brilliant at what it does. But when you rely on it to do the hard parts for you, you own the consequences.

So I rolled up my sleeves and wrote the parser myself.

This brings us to the next chapter: adapters — how to take this beautifully awkward data and make it usable inside the genealogy app.