Making Sense of It

We’ve now unravelled the form, decoded the mechanics, and survived the output format. At this point, we know:

- How the form works (a bare

search.plcall with no parameters gives you the blank slate) - That we don’t need to click buttons or type into boxes — we can just POST the parameters directly

- How to parse the returned HTML/JS hybrid and extract the compressed

searchData

So now the question becomes: How do we actually use this inside the “search the web” capability of the research agent?

This is where the fun begins. And by “fun,” I mean the kind of fun that makes you wish you’d built something else.

Integration

If you’re looking for a real challenge, this is the section you’ve been waiting for.

Even in its early form, the research agent has two very different starting scenarios:

- “I have a person — find me their record(s).”

- “I don’t have a person — find me possible record(s).”

These are not the same problem. They’re not even cousins.

Scenario 1: Known Person → Find Their Records

Here we:

- Resolve the person in the GEDCOM

- Extract their details

- Fill in the FreeBMD search parameters

- Use those details as anchors for filtering

This is structured, predictable, and almost civilised.

Scenario 2: Unknown Person → Find Possible Matches

Here we:

- Extract details from the user’s question

- Plug them into the search

- Hope the user didn’t ask for “John Smith born sometime between 1800 and now”

This is chaos. Controlled chaos, but chaos nonetheless.

Before either scenario can proceed, we must answer a more fundamental question:

Is this a research task or a web‑search task?

If it is a web search, we must also decide:

- Which website to search

- What parameters does it accept

- Whether it’s on our allow‑list

- Whether the LLM is about to hallucinate a website that doesn’t exist

To keep things sane, I found it easiest to use different prompts for research vs. web‑search. Our focus here is the web‑search path.

Adapters

Today we’re talking about FreeBMD, but it’s just one of many potential sources. FreeReg (parish records), FreeCEN (census), and countless others could join the party.

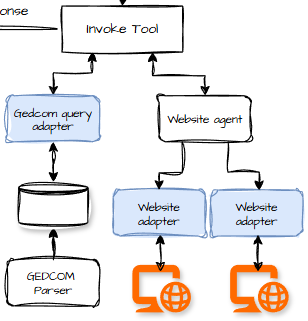

Originally, my architecture looked like this — a simple “invoke tool” model, because I was thinking of everything as a tool, including myself.

But as the system evolved, so did the complexity.

Of course it did.

Transforming

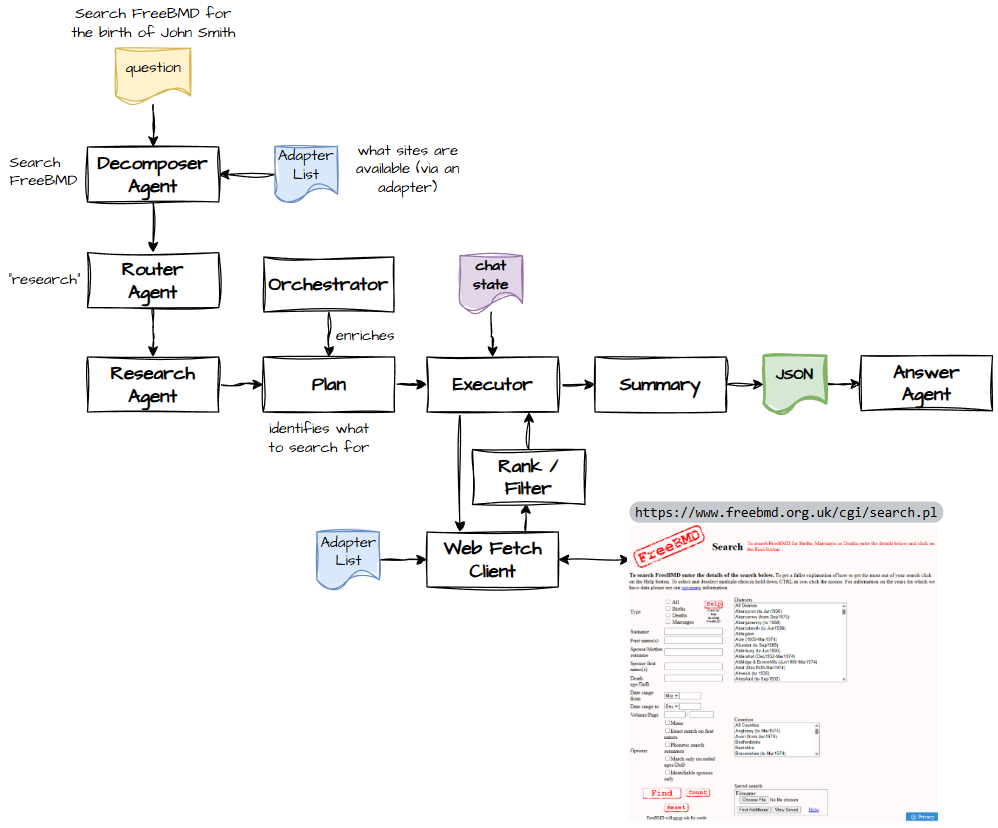

The decomposer agent takes the user’s question and produces a structured plan: people, places, dates, and what to look for.

Our job is to execute that plan.

Let’s assume everything goes smoothly (I know, I know — but let’s pretend). We’ve queried FreeBMD via the adapter. We’ve received data.

Now what?

1. Cap the number of records

FreeBMD can return up to 3000 records. The LLM cannot. If you feed it 3000 rows, it will simply fall over and return a 500.

2. Rank the results

Not all matches are equal. Some are perfect. Some are “close enough.” Some are “I don’t know who this is, but it’s definitely not your ancestor.”

3. Express confidence

Users need to know whether we’re 95% sure or 5% sure. Otherwise, they’ll assume the AI is omniscient, and that way lies madness.

The Middle‑Name Problem

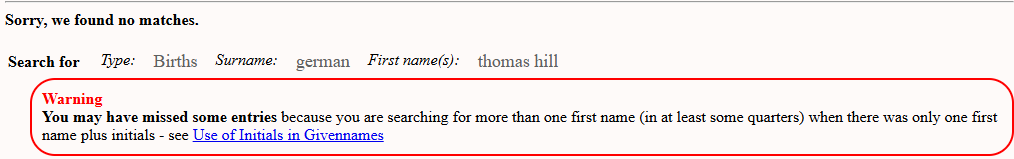

FreeBMD is inconsistent with middle names:

- Sometimes they’re spelt out

- Sometimes they’re initials

- Sometimes they’re missing entirely

If we’re not careful, my own grandfather disappears from the results.

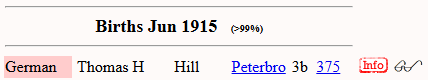

But once we account for initials:

FreeBMD even documents this: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/givenname-initials.html (EXTERNAL)

In 1915, 63% of entries used initials. This matters. A lot.

The Quarter Problem

Births, marriages, and deaths are indexed by quarter. But life doesn’t always cooperate.

If Grampa Joe is born on 20 December, his parents might not register him until January. So he appears in Q1, not Q4.

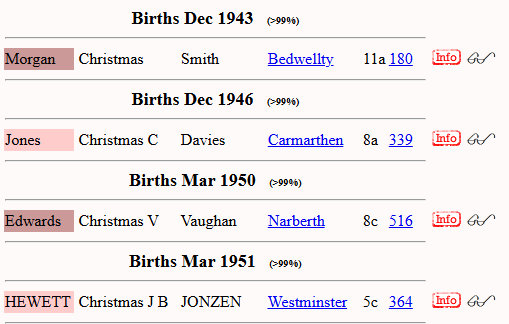

Like these Christmas babies:

This applies to deaths and marriages, too.

The Name‑Change Problem

People die with different names than they were born with.

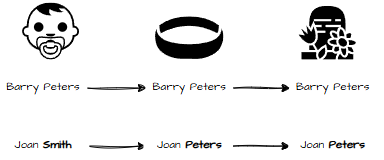

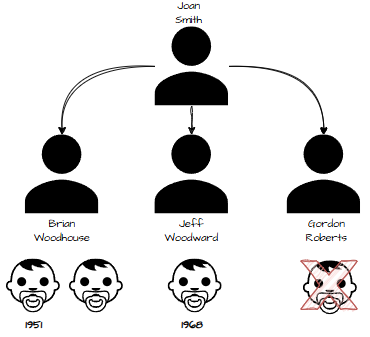

- Born Joan Smith

- Marries Barry Peters

- Dies Joan Peters

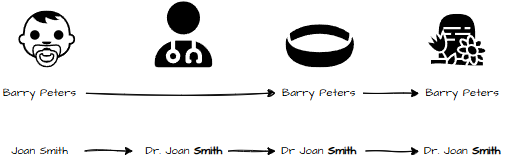

But sometimes the name doesn’t change — for example, doctors who keep their professional name after marriage.

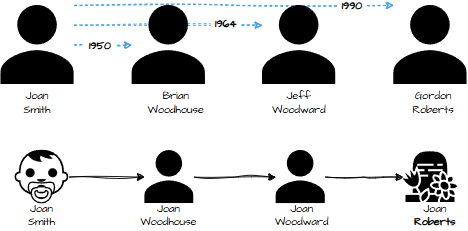

And sometimes people marry multiple times:

Which surname do we use at death? It depends on:

- Order of marriages

- Whether a spouse died

- Whether there was a divorce

- Whether she reverted to her maiden name

- Whether children were born in each marriage

We can infer some ordering from children:

Genealogy is detective work. It’s logic. It’s inference. It’s patience.

And occasionally it’s shouting “WHY ARE YOU LIKE THIS?” at a 19th‑century registrar.

And Then the User Asks for Everything at Once

“Find me the birth, marriage, and death of John Smith.”

This breaks:

- Ranking

- Prompt structure

- Token limits

- My will to live

And remember: FreeBMD can return 3000 rows. The LLM cannot digest 3000 rows. It will simply keel over.

Closing Thoughts

This is the start, not the end. FreeBMD is just the first external research tool to be integrated. Many more will follow.

And if you’re thinking:

“Dave, if I have to type ‘search freebmd for John Smith 1970,’ why not just go direct?”

A fair question.

The answer is simple:

The app is greater than the sum of its parts.

The AI isn’t just forwarding your query. It’s combining:

- What it already knows

- What it needs to know

- What it can infer

- What it can fetch

- And how confident it is

This isn’t about replacing FreeBMD. It’s about empowering the AI to answer complex genealogical questions that require both reasoning and data retrieval.

Without tools, the AI is guessing.

With tools, it becomes a researcher.